Being able to effectively, authentically, and empathetically discuss contentious issues and the more vulnerable parts of yourself is a vital, life-affirming skill. Arguments with those we love don’t have to be shouting matches, or be punctuated with slamming doors, or leave you unfulfilled, unconnected, and lonely in your relationships. Conflict is not your enemy; it is the opportunity to acknowledge, negotiate, and reconnect.

Outlined below is just one possible path from arguing to discussing; a series of planning and discussion exercises that you can undertake individually and with your partner, or another loved one in your life, that will lead you both out of the more detrimental arguments to emotionally sincere and productive conversations that confront and resolve issues.

Planning Stage

The planning stage, the part before you attempt to revolutionise your arguments, is an important one and consists of two major components: stocktaking and scheduling.

Stocktaking

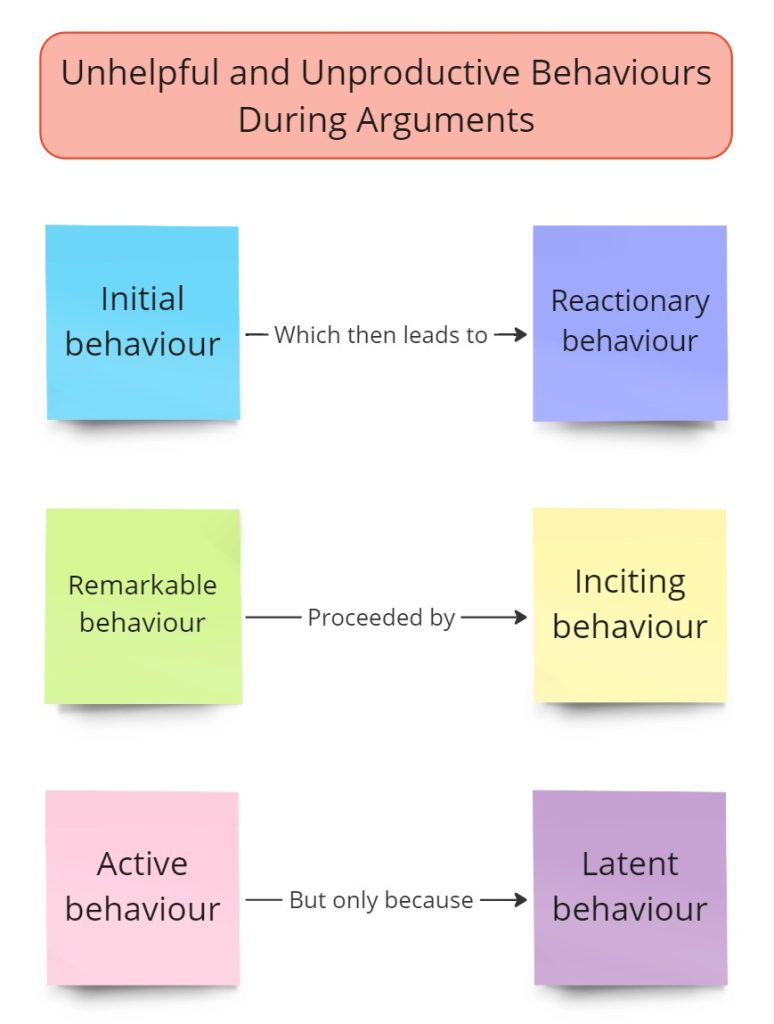

When people argue, they can sometimes fall into patterns of behaviour. The stocktaking part of this exercise aims to begin a physical resource, namely a list, that you and your partner can build on, alter, and refer to later on during the discussion to help take account of these unhelpful, unproductive behaviours: the existing barriers in your relationship to you both experiencing more connection-building and productive conflict. So, the aim here is to end up with a list of behaviours that derail your arguments and make them unproductive.

Be thorough

- Mentally replay your previous arguments

To start this list of behaviours, think back to the last few arguments. As you replay them, write down the more detrimental behaviours that you believe cause the argument to go on longer and cause unnecessary hurt to the other partner. Be as thorough as you can.

- Try to think in “redirections”

Secondly, take each behaviour and try to think of a helpful redirection; what is the counter-behaviour to the issue at hand? What behaviour could you or your partner be doing more of to lessen the frequency or effect of a particular behaviour you have listed.

For example, one of the things you wrote down on the list was that your partner does something that inflames arguments like name-calling and when this happens, you tend to start to raise your voice and bring up past events that make them feel bad. In this moment, try to think of a counter-behaviour you could do more of that would lessen the frequency or effect of them calling you names. Is there a way to communicate with your partner in order to regain control and limit the effect of that unhelpful or unproductive behaviour they are demonstrating?

To be able to do this, it may be helpful to frame the behaviour as ultimately a choice your partner is making, maybe not because they want to but because they’ve never learnt how to make any other choice; if they make that choice in an argument, what choice would you like to make? Instead of walking the old path and raising your voice, you could choose to have a firm boundary about what makes you feel disrespected – which you have communicated with your partner prior to the argument – and then you enforce that boundary by calming taking temporary space from your partner and not immediately continuing to argue after that boundary has been disrespected.

A different example of an unhelpful behaviour could be you might not be forthcoming about issues when they arise and hold them in until you emotionally explode over a smaller issue. A helpful redirection of that behaviour might be recognising your partner (and yourself) need to take additional steps to actively cultivate a culture of honesty and openness in your relationship.

In contrast, you may realise the withholding issues behaviour might be in part because of a behaviour that your partner demonstrates, for example, when you finally bring up the issue to your partner, they don’t take the issue seriously or they act aggressively. We will talk about inciting behaviours more in the next section, but if this is the case – that there is reactionary or latent behaviour that encourages the initial/active behaviour to keep happening – then try to do the redirection exercise on both behaviours.

For the withholding behaviour, you might have to seek more reassurance that bringing issues forward is going to be met with an atmosphere of openness and collaboration. For the not taking issues seriously or acting aggressively behaviour, you partner might want to build a practice of counting to 10 when you come to them with an issue. During this time they might routinely ask themselves a thought-provoking question before acting, something like “Do I want to bring my partner closer in this moment or do I want to push them away?”

- Try to identify inciting behaviours and patterns more generally

For all the behaviours you wrote down, now attempt to think back to see if you can identify an inciting behaviour/s that led up to the behaviour you wrote down. For example, your partner might exhibit name-calling but only when you falsely threaten to break up. Write down any inciting behaviours that occur to you in the list.

Alternatively, there may be some other patterns of behaviour in the way that arguments between you unfold, for example, you might go through a stage of denial at the start of every argument that causes your partner to be more defensive of their point of view than they would ordinarily. Any patterns that you think of would also be useful to make note of in this list.

- Try to get an equal representation of you both on the list

For the final thought exercise in trying to stocktake, work to create a list that captures the unhelpful or unproductive behaviours of both partners as equally as possible. So if for example, you find yourself listing all the unproductive behaviours that your partner exhibits in arguments, you might try the above exercises of identifying opposites, inciting behaviours, and patterns, whilst also just being more self-reflective.

One way to do this is by thinking back to previous arguments you have had with your partner, ex-partners, and other loved ones in your life and working out patterns of when people in your life tend to be the most upset with you while in conflict. These could be overt behaviours, such as name-calling or storming off, but also more covert ones too. For example, ask yourself if there are any cycles of thinking that you find yourself in that affect your ability to support and be supported in an argument, such as, “My partner doesn’t want to listen to me” or “My partner is going to abandon me” or “My partner is being intentionally difficult, I just don’t want to argue”.

The more honest you are with yourself about all the ways you and your partner haven’t been putting your best foot forward in your arguments, the better you will understand the barriers to more productive arguments and the more likely you are, as a partnership, to overcome them.

Setting the right tone

You might consider writing the list with the behaviours or issues as they are; without assigning them to either partner. Making the issues and their “opposites” anonymous so to speak is just one way to set the right tone for the discussion with your partner. Not assigning any issue to either partner at this stage is just one way of decriminalising this process and putting forward the intention for the discussion to be honest and exploratory. The time to discuss individual culpability and how you both can show up more productively as individuals will take center stage later on, so keep this beginning as open but honest as possible.

Everything you both do from this point forward should be to encourage both of you to enter this discussion space with the notion of love, teamwork, and humility. This means being candid about the issues you experience in conflict without playing the blame game. You might try conceptualising it instead as the responsibility relay.

Scheduling

With any conversation in your relationship that you expect to be especially emotionally taxing, it is important to give both you and your partner the best chance to make the most of the conversation and be the best version of yourselves during the conversation. This means having an awareness of your time, your processing preferences, and the state of your emotional resources.

As such, when deciding on a time together with your partner, think about your schedules, your sleep patterns, and the way you manage stress. For example, will you want time after to process the conversation, or would you prefer to be going into something else?

It may also be wise to think about the amount of time you are allowing yourselves for the discussion. Is it sufficient time to be able to have the full conversation or would you both find it easier to have the conversation in multiple sittings?

Before you approach them, attempt to predict your partner’s responses to these different elements so that you can come up with a suggested time for your partner to accept or renegotiate. Once you are ready, broach them for their consent to this discussion at a time when they can fully comprehend what you are suggesting, with a phrase such as:

“I have been thinking a lot about how our last few more heated discussions have gone and I want to be able to better maintain our connection in those moments, even when we’re upset with each other. Would you be open to talking more about that with me? I’d love to hear how you feel I could better support you and vice versa and so I was thinking we could talk about it tomorrow/on Monday on your day off, maybe in the morning, what do you think?”

As mentioned, be mindful of their emotional and psychological head space when asking this and be ready for them to suggest a different time, especially if they are factoring in changing variables such as their stress level, and welcome this new suggested time if it works for you. It is important for the productivity of this and any more heavy-duty discussions that both of you can remain civilly in the same room together, speak with kind honesty, and both be emotionally ready, consenting, and willing to discuss how to improve the way you both relate to each other during arguments.

For the discussion with your partner

Discuss conflict styles

What?

Like the more well-known love languages, it can be useful to try and broadly frame and categorise the way we most often act in conflict. This can be a potential indicator of our attachment style but here, for these purposes, we just want to identify any potential patterns in the way we act when we are in conflict so we can prepare our partners and identify potential risks to our feelings of relationship security, support, and respect.

Why?

One of the biggest reasons to discuss conflict styles and what they mean to you and your partner is to enable communication, avoid confusion, and provide reassurance to both partners at a time when you both feel incredibly vulnerable.

What you may want in any given moment in a conflict situation may be subject to change, but opening up this dialogue with your partner about the ways they most often engage in conflict and why that is may be helpful to understanding each other’s behaviour when you are more heated and potentially thinking less clearly.

How?

An easy way to start doing this is to be aware of and discuss with your partner your conflict style and theirs. As with everything, how a person argues can vary depending on, for example, the level of emotional strain, but on the whole, when an issue arises, do you usually…

- want to discuss the issue with your partner straight away? Is it difficult for you to concentrate on anything else? Does having conflict make you more eager to talk to your partner? Or;

- want to have a timeout? Do you prefer to have time away from your partner to decompress? Do you prefer to be able to calm down, and come back to conflict?

For example, on balance, you may find that you prefer to discuss an issue in a more timely manner so that you aren’t worrying about the issue and/or that things with your partner are resolved more quickly.

Now, your partner might be similar, or in fact, they might be the exact opposite. Either of you might feel that, on reflection, you are often overwhelmed with an issue at the beginning, which means you often favour taking time out of the immediate space with your partner so you can cool down and formulate your thoughts in order to be in a better emotional space to have a discussion.

Both of these and any variation in between, are valid responses to conflict. This is about discussing where on that spectrum you are most often and comparing that to where your partner is.

Work out a plan for the difference in conflict styles, regardless of whether you have the same style or not

Now, knowing more about what both of your conflict styles are, this next stage is to create a plan to accommodate each other’s styles into your relationship and future conflicts. This is important whether you have the same style or not because, as mentioned, there may be times when you or your partner may break away from your typical style.

In this stage, it may be good to identify a phrase that communicates the person’s emotional need whilst also providing reassurance for the partner about why they need it.

For example, in the case that you need space from your partner, you might want to prepare a phrase like:

“I appreciate we have x issue to discuss. I would like to take some time now in the other room to process and make sure I’m in the best head space possible to have this discussion. While I’m taking that space, I want you to know that I love you and I look forward to hearing your perspective and to resolving this.”

Alternatively, in the case that you are stressed about your partner needing space while they calm down or process, you might consider preparing a phrase like:

“It’s understandable that you’re upset and need space right now to calm down. Before you go, would you mind giving me a hug and/or letting me know that we’re okay and/or giving me a rough idea of when to check in with you again? This will help me to support you in giving you the space you need without me becoming overly anxious about sorting this issue, about your feelings towards me, or about the security of our relationship.”

Obviously, you can adapt these to your specific situation but a potentially useful formula to communicating a need that arises from your conflict style is:

- Acknowledge the importance of the issue that you are arguing over.

- Tell them your emotional needs, e.g. space, reassurance, etc.

- Outline the benefit to your partner of recognising your need e.g. you will be able to better support them in fulfilling their need.

- If required, reassure your partner of your feelings towards them, your interest in their perspective, and your belief that you can both work together to sort out the issue at hand.

If one partner is especially anxious about letting the other have space, after the reassurance, it may be useful to add a suggestion of an activity that redirects their focus. This is something you can discuss ahead of time, and in the argument, this could look like, for example:

“While I take that time and space to reset, why don’t you stick the kettle on, and/or why don’t you watch that YouTube video you were talking about watching and/or insert proven de-stressing activity here”

Ultimately, this stage is about making sure you both are aware that either conflict-style response can be understood in future conflicts, not as a comment on the emotional investment in the relationship but as part of the processing of the issue/conflict. What I mean by this is that if both partners can communicate their needs lovingly, clearly, and respectfully, then the other can calmly, respectfully, and with reassurance, support their partner through it. All needs can then be acknowledged and fulfilled while protecting the sanctity, serenity, and security of the relationship.

Identify triggers/risk factors that lead to escalation

Identifying triggers and risk factors that lead to escalation in your discussions with your partner could look like you both sitting down and starting to think about what really aggravates you both individually and together and taking the time to discuss those triggers and risk factors with one another. Also, consider taking this time together to examine the effects of those triggers and risk factors for escalation, how you individually respond to the other’s words and actions, and how that leads to escalation.

Having this conversation outside of an argument setting can do wonders for prepping you both and putting you in a more understanding and empathetic mindset before emotions are heightened and the ability to talk calmly and clearly is strained.

Outline parameters that you both agree on

What is parameter setting?

Parameter setting is about setting a code of conduct so to speak. Think here of more general relationship values, for example, respect, honesty, kindness, and mutuality, that you both would like to see more of in your arguments. In your specific discussion, you might consider accounting for factors that came up in the stocktaking section outlined earlier. Parameter setting can help to stem reoccurring behaviours that consistently drive up the tension between you and your partner during conflict and that detract or distract you both from talking about and resolving the issue at hand.

Examples of types of parameters

The following are some examples of the types of parameters that may be useful:

- What do you both see as the preferable window between when an issue occurs to when it is raised, e.g. a day, two days, a week. This is to place an expiry date on issues but to encourage timely honesty between you as to when issues do arise.

- Outlining less helpful, more detrimental behaviours that you could both try to avoid e.g. name-calling, storming off, bringing up multiple unresolved arguments in one sitting, falsely threatening breakup etc.

- Expressing upset in clear terms, not through your subjective perspective. For example, instead of assuming what the other person thinks and feels, such as: “You just don’t care about me!”, a useful parameter could be to encourage both of you to rephrase and clearly evidence and frame your feelings to the best of your ability, for example: “When you do/say …, it makes me feel …”. If you are struggling to point to a specific cause/behaviour/evidence for your feelings towards your partner, this can be a sign for you to think about and examine your upset more deeply to understand whether you are not noticing or subconsciously ignoring when your partner upsets you or whether there are factors outside of your partner’s control influencing how you feel about them.

Getting agreement

The important thing to close on in the parameter setting part of your discussion with your partner is to get mutual agreement and commitment to adhering to the parameters that have been discussed. This is true both of conflict parameters and of relationship expectations more generally. Once you have the mutually agreed upon conflict parameters, a good first step to showing commitment to them as a partnership could be to write them down in a list that you both have access to, can refer to, and mutually alter at any time.

Set individual focuses

While going through this process, you may both realise that there are multiple things either of you or both of you need to work on, but don’t be disheartened; this is a wonderful effort you are undergoing for each other and for your relationship.

If it helps, write down a ‘wish list’ so to speak for what you both would like to work on and then start slow. Set out what you would like to focus on; this may be one thing, two, or even three.

This type of behavioural change can be challenging to implement so if it helps, feel free to start slowly. Proceed in future arguments with the hope that you can implement all the changes you both have outlined, but the determination in both partners to implement at least one of those changes each.

Create backup plan

Especially if the first few times are especially heated and the changes are particularly hard to implement, a de-escalation strategy is a good thing to have. A good place to start is to fit your emotional toolbox with skills such as reflecting, reassuring, and validating the feelings of your partner as well as recognising how your words and actions can impact them.

Next, you might try a respectful reminder of the conversation you both have had.

When one or both partners are really struggling to adhere to the parameters, you might then consider working out some interruptive behaviour solutions. Any behaviour that you have found to help you both calm down can work here. Some examples are:

- Sitting in silence and focusing on your breathing, for example, for a minute

- Removing yourselves physically from this space and be in separate spaces for a short while, for example, 5-10 minutes

To plan to implement this effectively, it might be good to work out a pre-prepared phrase that either can say when needed. For example, this could look like:

“Hey, we had a really great conversation about how we wanted to handle our more heated discussions and it feels like those changes we agreed to are particularly difficult to stick to right now, so let’s sit in silence for a minute and just focus on our breathing while remembering what we talked about and then restart.”

Additionally, you could have several stages of a backup plan, so, again as examples, do the breathing and if that doesn’t work, then be in separate spaces for a while, to eventually be able to be in the same space again and discuss this issue calmly within the parameters to which you both agreed. Setting intentions and building in backups and also talking about why those backups might be needed can help you both process and support each other more effectively even in those most heated of moments.

Closing thoughts

These types of conversations can be very tricky and setting up good, safe conflict boundaries can seem challenging, but you may find them to be worth it to be able to come together to support one another regardless of what challenges you have faced, you currently face or you may face in the future.

The outlined path above is intended to provide a starting block and help as many people as possible but it is difficult to be able to cover all possible scenarios. As a result, there is a short FAQ below, and if that still leaves you wanting, then please consider a one-to-one meeting with me, which you can request here.

FAQs:

- This seems like too much work and too much time, is this worth it?

Any time you invest in your relationship, you are not only investing in your partner but also you are investing in yourself too. Learning how to lean away from arguments and lean into productive discussions is a skill you can take into all areas of your life, personal and professional. In terms of your relationship, being able to cut down on the more damaging behaviours and shouting matches can not only drastically reduce the length of future arguments but also build an incredibly strong connection with your partner. This is because cutting down on them makes space within these more difficult conversations for opportunities for your partner and yourself to achieve increasingly deeper states of emotional vulnerability and connection to one another.

2. Am I not allowed to express my anger and upset with my partner?

Of course, you should express, upset, hurt, and anger; that is a key part to both understanding and forgiveness. This is just about reframing and repackaging how you both handle and express your emotions to one another. It is about sharing that with your partner in a way that is healing and productive for both of you. It is all about giving yourself the best chance to express yourself and be heard and supported by the person you love. Similarly, it is about giving your partner the best chance to understand, acknowledge what has happened, expand on it, and show you how much they support you. It makes the issue clearer and allows you both to come together to readjust and plan to navigate this issue better in the future. During all of this, you are both working with respect, care, clarity, and honesty that serve and protect the relationship you share.

3. I struggle to not fly off the handle and to implement the changes, is this not for me?

An ability and willingness to embrace change is key to self-growth and self-growth is key to maintaining happy, healthy, and fulfilling relationships. Ask yourself in those moments when you are more “activated”, triggered, or in your feelings, what stories are you telling yourself about yourself or your partner, or your relationship? Examples could be:

- “They don’t listen to me because they don’t find me interesting enough so I’m going to resist telling them how much they’ve upset me”, or;

- “They start shouting because they think they’re right and think I’m stupid so I’m going to shout louder”, or;

- “They don’t care about me, just like everyone else, so I’m going to use name-calling to push them away”, or;

- “They are never going to understand me so I am going to refuse to be vulnerable or tell them how they make me feel”.

Take care especially to go through the Triggers section above and work pre-emptively with your partner to identify where your more “activated” moments usually begin. Talking about this and developing a plan for how you both are going to work to better support each other in these moments can be a profound source of connection and encourage greater emotional openness and regulation in your relationship and individually going forward.

Moreover, when you feel more out of control in your response what is the situation that is playing out in your head and when is the earliest time you can remember feeling like that? It might be with a particularly argumentative primary caregiver, such as a parent. It might be a family member or a friend or a previous partner. Sometimes, when we struggle not to go down a particular emotional path especially repeatedly, we may not be fully present in the current argument and instead are living a previous narrative or situation with someone we loved or a key person of influence in our lives. Recognising these types of emotional and relationship patterns can be helpful as a first stage of the process of overcoming some of our inbuilt biases and traumas and can help you from continuing those cycles with your current and future partners.

4. If my conflict style is wanting to resolve the issue as soon as possible and my partner’s is space, how can we realistically satisfy both?

As described above, the partner who needs space might try practicing clearly and reassuringly communicating that need for space to their partner. In your need to sort it out as soon as possible, I would suggest reflecting on that and working out where you think that need stems from. Is there something in your specific relationship dynamic that makes giving them space tricky or do you find conflict in general particularly stressful and need that reassurance? Try using the phrases suggested in the Conflict Styles section above and also think for yourself what type of reassurance could your partner provide you with before taking that space that would help you feel calmer and more able to support them in their need for space. What type of reassurance usually helps you to feel calmer? For this, you might look to your love languages as a helpful starting point, for example, physical reassurance in the form of a hug, or verbal reassurance in the form of words of affirmation about their feelings towards you and the relationship.

5. My partner needs an unrealistic amount of space or time to come down during our arguments, what do I do?

Conflict can bring out our most basic, primal fears. Often those fears relate to being vulnerable with our partner and maintaining a feeling of security within ourselves. When our partner takes space and takes, what we see as, an exceptionally long time to do so, it can activate in us our more anxious or avoidant mindsets. When your partner takes a long time to come back to you, is the stress you are feeling ‘a’ or ‘b’:

a. due to having to wait for them while they take their space?

If so, discuss with your partner about their space. Do they take it to gain perspective on the issue or to de-stress? Is there anything that they can think of that usually helps with de-stressing that they don’t usually do when taking space in a conflict that they can employ in those moments to help them along, for example, meditation, listening to music, reading affirmations, reading a helpful note from a best friend or loved one prepared ahead of time.

b. due to not knowing how much space they will need or when they will be ready to come back and continue talking with you?

If so, think about having your partner give you an idea of time so it isn’t so open-ended. Then know that relationships work best with communication, so ultimately communicate the stress to your partner and troubleshoot with them. Even if they can’t give you an exact idea of when they will be ready to discuss the issue again, maybe suggest having at a minimum a time for when you will both check in with each other to check progress and readiness to continue the discussion, for example, “let’s check in with each other in 10 minutes to see how we’re getting on and whether we’re ready to begin discussing this issue again”

5. My partner doesn’t want to have this discussion with me to improve our arguments, what do I do?

Firstly, identify whether this is an assumption that you have or whether they are truly resistant to self-development in this area and/or others.

To do this, analyse your previous discussions in this area

If there is a possibility that they are open and they have not explicitly and openly rejected the idea of working to improve your arguments, then bravely broach this conversation with them with kindness, openness, and hope.

However, if they are truly resistant and have stated this to you, then look to identify your previous responses. It is important to assess whether you have clearly and calmly stated that this is a problem you see in your relationship and actively choosing to not improve how you argue is damaging to you, your partner, and/or your connection and your relationship.

If you have not clearly stated your concerns and they are not aware that this is a sticking point, because you have not voiced this to them, then make efforts to have a conversation with them, exclusively focused on this topic. In this conversation, explain why this improving the way you both argue, in a calm, loving, and clear way. You could say something like “These types of conversations can be difficult to have but it is really important to me that we both feel safe and confident in being able to come to one another about issues that we have and I don’t necessarily feel that is true right now. It would therefore mean a lot to me if you could open yourself up to discussing this. Together, I would like us to evaluate how we engage in conflict now and how we hear and understand each other better to engage better in conflict together in the future.”

If they are still resistant and unwilling to engage, then make clear both the emotional and relational impact that is having. You could say something like “It makes me sad to hear that you don’t want to engage with me about this. I understand this is very confronting and that these types of conversations aren’t for everyone. However, it is incredibly important to me that I am with a partner who is ready and willing to work to improve our conflict patterns and our relationship. It is starting to sound to me like that is not what you want from a partnership, is that true?” In this, you want to start to hint at the stakes of their continued decision to not engage. The key here is to understand that you are in charge of your own boundaries and while you cannot force them on others, you can express them and then, if your boundaries are not respected, you can remove yourself from the situation or relationship.

If developing your relationship and yourself is something you are committed to and your partner continually refuses to have these discussions, then this may be the time to start thinking about parting ways. Though you may feel deeply connected and even love them, your partner may not be ready or interested to take on an emotional and relational development journey with you. Recognising this can be key to your future happiness, either by making it clear to your partner the importance of engaging in these types of conversations to your ability to stay in this relationship which prompts them to overcome their more conflict-avoidant tendencies or that, if they are still unwilling to participate, you are disappointed and deeply upset but ready to move on, which will allow you to find someone who will not only participate but instigate these types of healthy but challenging conversations.

More questions? Need more answers?

The outlined path above is intended to provide a starting block and help as many people as possible but it is difficult to be able to cover all possible scenarios. However, if you believe I have omitted something important, please don’t hesitate to reach out.

If you would like more clarity on a specific situation you are experiencing, or help long-term, please feel free to book in for your free 20-minute coaching consultation!

Leave a Reply